- Home

- Pam Muñoz Ryan

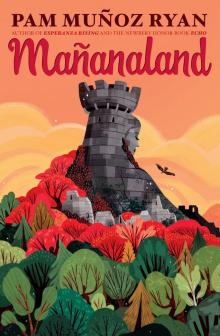

Mañanaland

Mañanaland Read online

To my mother,

Esperanza “Hope” Muñoz Bell,

for protecting me

beyond measure.

Title Page

Dedication

YESTERDAY

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

TODAY

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

TOMORROW

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

Somewhere in the Américas, many years after once-upon-a-time and long before happily-ever-after, a boy climbed the cobbled steps of an arched bridge in the tiny village of Santa Maria, in the country of the same name.

He bounced a fútbol on each stone ledge.

In the land of a hundred bridges, this was his favorite. When he was only a baby, Papá, a master stonemason and bridge builder, had carved his name on the spandrel wall for all to see.

MAXIMILIANO CÓRDOBA

On his bridge, Max liked the going up of it.

He liked that when he reached the threshold, the deck breached Río Bobinado in a long bumpy alley. He dropped the ball and dribbled it toward the middle of the deck, bouncing it off the sides of his dusty huarache sandals.

Here above the keystone, he could see all of his world before him and the river below, curving away from Santa Maria, looping back and curving away again. He moved his hand to mimic the river’s erratic path as it circled the islets and giant boulders. Why was Río Bobinado so indecisive?

Max glanced over his shoulder to make sure Papá hadn’t caught up. “Once …” he whispered, “… a gargantuan serpent as wide as twenty houses and as long as three states could not decide whether to slither west toward the ocean or east toward the mountains. As soon as the serpent chose one direction, the other seemed far more appealing. Back and forth it went, side-winding across the earth, its body leaving a huge chasm in its wake. The chasm eventually filled with rain and became the river.”

Satisfied, Max smiled. This was his favorite spot to make up stories and wonder about big and bewildering things: How long it would take to grow up and become a man, if he would ever see what lay beyond the horizon, and why his mother left and whether he’d ever meet her.

Max knew that Papá didn’t like big questions of any kind, especially ones about the past or the future. Some of them even seemed to cause him pain. Max couldn’t count the times Papá had instructed him to “stand firmly in the reality of today or life will only disappoint you tomorrow.”

He pushed Papá’s words aside and gazed out at the village. The more prominent houses—greens, yellows, blues—hugged the riverbanks. The spire of the chapel, Our Lady of Sorrows, pointed toward the heavens. Citrus orchards and grape fields bordered the outskirts of town. Nestled in the foothills on dirt roads, modest white stone cottages perched like patient doves at roost. Max shaded his eyes until he spotted his. Was Buelo already cooking dinner with Lola at his side, begging for scraps?

He let his gaze continue upward toward a jagged cliff where a stone tower loomed. Everyone called the stronghold La Reina Gigante, the giant queen, because she looked like the most powerful piece on a chessboard. Max loved that wherever he went in Santa Maria, he could see at least the merlons and crenels of her crown, as if she was always watching over him. He even had a faint memory of sitting at her feet while red blossoms rained upon him. Had it been a dream?

The palace surrounding La Reina Gigante had once been majestic, too. But that was decades before the cannons of ancient armies demolished the roof, an earthquake unsteadied the walls, and a war in the neighboring country of Abismo forced legions of people to flee a dictator, using the ruins as a safe place to hide. Some said these “hidden ones” were poor innocents—women and children. Others said they were malicious criminals, filthy beggars,and the unwanted.

No one had ever seen a hidden one to know for sure. But it was rumored that their spirits returned each year on the wings of the peregrine falcon. Sometimes when heavy mist shrouded the hills and Santa Maria fell silent, their ghosts could be heard whispering prayers to the giant queen for her protection and guidance, as if she was a saint or a guardian angel. Everyone knew someone who knew someone who had heard them.

The entire property around La Reina Gigante and the ruins was fenced, abandoned, and off-limits. Only Papá had permission from the mayor to commandeer the rubble to build new bridges. For as long as he could remember, Max had begged Papá to take him to see La Reina and the ruins up close. He’d be a hero among his friends if he was the first boy to cross the haunted gates! Just because Papá didn’t believe in ghosts didn’t mean they weren’t there. Maybe this summer Papá would finally take him. He was almost twelve.

Max leaned over the capstones, warm from the afternoon sun, and waited for Papá to catch up. In the river, he saw half of his head reflected: a mop of black curls, heavy eyebrows, and caramel-colored eyes. Buelo called them tiger eyes and said they were a sign of strength and determination. Chuy called them leche quemada eyes, like their favorite milk and brown sugar candy. Some of the boys at school called them devil eyes. Max did his best to ignore them. But he wondered if the boys knew something about him that he did not. Was he filled with badness? Still, they were his mother’s eyes and one of the few things about her he could claim. That, and a tiny silver compass on a leather cord that once belonged to her. He patted his chest and felt it beneath his shirt.

As he tossed a pebble into the river, he let the rippling water turn his heavy thoughts to happier ones. School was out, and tryouts for the village fútbol team were in five weeks. Like all his closest friends, he dreamed of making the team.

Max picked up the ball and threw it at the parapet, letting it ricochet back so he could catch it. The bumpy stones sent the ball in unpredictable directions, forcing Max to hover and anticipate. He kicked it hard, and when it hit the wall and flew back at him, he batted it down.

“Bravo!” Papá yelled. “Don’t unsettle any of the facing though. Or I’ll have repairs.” His cheeks flushed with ruddy circles and his forehead wrinkled from his usual troubled frown.

“You know I can’t kick as hard as you,” said Max. Papá was broad shouldered and solid, a wall of strength and muscle. He and Buelo had both played goalie on Santa Maria’s national team, and Max wanted to one day do the same. He was already as tall as both of them, but scrawny.

Max kicked the ball up and caught it in his hands. “Do you remember that tryouts are next month?”

“It’s hard to forget when you remind me so often.” Papá almost smiled.

“I was wondering … My fútbol shoes are nearly too small and the toes will need wrapping soon. If I had a pair of Volantes, the ones with the fancy wings on the side, I’d surely make the team.” He looked at Papá hopefully.

“Your shoes are fine for now. And expensive ones that we can’t afford won’t make you a better player. A world of disappointment comes from wishing for what you cannot—”

Before Papá could finish, a falcon swooped overhead, low enough that both he and Max ducked. Its sickle-shaped wings were splayed and taut. The head and hooked bill stretched forward, bar

ing a white neck and speckled breast. They shaded their eyes, mesmerized by the silent flight.

“It’s so big,” said Max as it caught a current and soared away.

“Peregrine,” said Papá. “A female that has come back to nest.”

Whose spirit did it bring on its wing? wondered Max. “They say—” he started, then thought better of repeating the superstition. “They say they come back to the same spot every year.”

Papá nodded. “It’s true. But I haven’t seen one that large for a long time, and it is a little late to nest. Others have already come and gone.” He put an arm around Max’s shoulder and hugged him to his side. “Let’s go, slowpoke.”

“Me? Slow?” Max quickly dribbled the fútbol across the deck and called over his shoulder, “I’m going to meet Chuy at the field, and I’ll still beat you home because you have to stop and talk to everyone!”

“Come home right after. Buelo went fishing this morning and dinner will be ready in an hour or so. I don’t want to have to come looking.”

“Okay!” Max yelled back. Papá had only recently allowed him to go to the field on his own. Max didn’t want to give him a reason to take back the small freedom, or upset him. Saturday was Papá’s night out with his friends and Max’s night in with Buelo, and he wanted to keep it that way.

By the time Max reached the bridge’s landing, he felt as free as the soaring peregrine. Summer was the infinite sky before him. He had months to swim in the water hole, play fútbol with his friends, and get ready for tryouts. Tonight, he would go to sleep with a belly full of fish after an evening of trading stories with Buelo—fantastical tales about dragons and serpents, or river monsters and trolls …

He clutched the ball to his chest and jumped toward the bank, taking two steps at a time.

On his bridge, he even liked the going down of it.

The field was more of a bald spot than a grassy park but good enough for practice or a pickup game. Real games were held at the secondary school a few miles away.

A group of boys warmed up, juggling balls knee to knee or passing to one another. Now that Max and most of his friends were turning twelve, they could finally try out for the village team. Santa Maria was crazy for fútbol, and the local team had won the last two regional championships. People flooded to their games. This year, the league was sending a new coach to Santa Maria. All eyes would be on him and his players.

Chuy waved Max onto the field.

“Your hair! What happened?” said Max. Yesterday Chuy had a mop of curls like Max. Now it was buzzed close to his scalp.

“It was so long, my sisters were trying to braid it.”

Max laughed. He could picture the three little girls doing that. Even though they could be annoying, and Chuy complained about them all the time, Max would have loved a baby sister or brother to whom he could tell stories, give piggyback rides, and share secrets.

Chuy ran a hand over his shorn head. “Besides, I don’t want anyone to confuse you and me.”

“That will never happen!” said Max. Chuy had a broad chest and was solid to the core, an avocado straight from the tree. Max was a pointy blade of agave.

“Come on.” He herded Max to the field where Ortiz and Guillermo were kicking balls back and forth.

“Max!” called Ortiz. “Come to pay your respects to Ortiz the Great?” He liked to remind the boys that he was the son of a councilman, lived in the biggest house in all of Santa Maria, and was older by almost a year. His voice had recently changed and sounded like a man’s. He was a head taller than the rest, with thick muscular thighs. And there were wisps of hair already growing above his lip.

“The great what?” said Max. “Fanfarrón?”

All the boys laughed because it was true. He was a braggart.

Ortiz shrugged. “If you are the best, you should tell the world.” He shook a finger at Max. “You’ll see. Let’s play.”

Chuy held up his hands to make an announcement. “Okay, everyone! Ortiz and Max are goalies. My talent on the field is up for grabs!”

The boys jeered and quickly sorted teams.

Max and Ortiz went to opposite ends of the field where makeshift goalie cages had been hammered together from wood scraps. Someone placed a ball midfield and took the kickoff. The boys ran hard, some barefooted, some in ratty shoes with no laces, some in huaraches, like Max, saving their fútbol shoes for the real games during the season. Max protected almost every shot on goal. Ortiz missed many of his, but when he did get the ball, his throws and kicks were long and hard.

They played until the sun was low. Then Max, Ortiz, Gui, and Chuy huddled around an old water spigot sticking up from the ground and gulped long drinks. As they headed back toward the bridge together, Ortiz announced, “I have news. My father talked to—”

“Shush …” hissed Gui, spreading his arms out to stop them. He pointed to a tree arching over the road. “Look.”

The falcon sat on a branch, chest puffed, preening its feathers.

Max kept his voice low. “Female peregrine. I saw it earlier.”

The bird leaned forward.

“She’s watching us,” whispered Chuy.

“She’s huge,” whispered Ortiz.

Max nudged him. “Don’t worry. She only eats pigeons.” As they inched closer, the falcon opened her wings and lifted in a languid, elegant arc, her yellow legs like two spent arrows tucked tightly beneath a fanned tail. She sailed toward La Reina Gigante.

In a somber voice, Gui said, “She has brought the ghosts of the hidden ones. That’s what my brother says.”

Ortiz smirked. “You’ll believe anything.”

Gui shook his head. “There were hidden ones. Guardians helped them run away from Abismo. Their spirits return on the wings of the peregrine.”

Max grinned, recalling how he and Chuy used to put on capes and masks and pretend to be Los Guardianes de los Escondidos, the Guardians of the Hidden Ones. He picked up a stick, raised his arm as if holding a sword, and lunged forward. “Gui’s right. The hidden ones fled Abismo because of a cruel dictator. The guardians bravely guided them through Santa Maria to safety.”

Chuy picked up a stick, too, and fenced with an imaginary attacker. “The guardians wore disguises and were invincible. No matter the danger, they carried on to help those in need.”

“Stop!” said Ortiz. “You’re both acting like you’re five years old. Want to know the real truth?”

“That is the truth,” said Max.

Ortiz shook his head. “My parents said the hidden ones were dangerous—murderers and thieves—the worst of the worst. Why do you think they were cast out of their own country? You don’t see any of them living in Santa Maria, do you? That’s because if they’d shown their faces, they would have been driven out of town.”

Chuy shook his head. “But the guardians—”

“—were criminals, too,” said Ortiz. “They broke the law by protecting the hidden ones. If they’d been caught, they would have been arrested and thrown in jail. But what does it matter? That’s ancient history. Does anyone want to hear my news? About the new coach?”

Max and Chuy tossed their sticks aside and crowded close to hear.

“Okay, okay,” said Ortiz. “My father talked to my cousin who manages the fútbol clinics in Santa Inés and has friends in the league. Our new coach is Héctor Cruz.”

Gui held up a finger. “Héctor Cruz? He’s great! When he played pro, he broke the national record for most goals in a championship game.” Gui may have been the youngest and smallest of all the boys, barely old enough to try out for the team this year, but he knew fútbol on and off the field.

“Let me finish,” said Ortiz. “He has lots of contacts with the higher-level teams so he’s a good one to impress. My cousin said Coach Cruz is strict about the league rules. Just to register for tryouts, everybody has to be the right age and prove residence.”

“What does that mean?” asked Max.

“Your address has to be in S

anta Maria, and at least one parent has to live with you,” said Ortiz. “So kids from other towns can’t take spots from us. And you have to prove your birthday so no one older can play in our league. Otherwise it’s not fair.”

“Remember when we played the team from Valencia?” said Gui. “Everyone knew the center forward wasn’t eleven!”

“He looked like he was old enough to drive!” said Max.

Chuy laughed. “Or get married.”

“But how do we prove it?” asked Max.

“Birth certificates,” said Ortiz. “Of course, then you have to make the team. And the competition will be tough.”

They all nodded.

“Anyone up for practicing tomorrow?” asked Chuy. “Max, maybe your father can come and give us some pointers.”

Before Max could agree, Ortiz threw up his arms. “Are you going to let me finish? I was going to tell you that my cousin has empty spots in one of his summer clinics. He said I could come and bring some friends. No tuition either. We would take the bus to Santa Inés every day during the week until tryouts. Are you guys in?”

Max’s and Chuy’s mouths fell open. The clinics had the reputation of being skill builders—drills and scrimmages under the watchful eye of coaches all day, five days a week. Players couldn’t help but have an advantage at the tryouts.

“I know I can convince my parents,” said Gui. “I’m definitely in.”

“Me too,” Chuy echoed.

“I’d give anything to do that,” said Max. “I’ll ask when I get home.” He hoped he could convince Papá, who found a reason to say no to everything.

“I’m going to Santa Inés tomorrow and staying the night with my cousin before the first day of the clinic. Héctor Cruz is coming for dinner.” Ortiz strutted. “Always good to know the coach personally, right? Otherwise, I’d ride up with you commoners on the bus Monday morning.”

Chuy rolled his eyes at Max.

Ortiz dropped his ball and dribbled forward. His footwork was quick. He spun around and headed back toward them, catching the ball with his toe and popping it up into his hands. “Just call me Nandito, the greatest footballer ever.” He bowed.

Paint the Wind

Paint the Wind Becoming Naomi Leon

Becoming Naomi Leon Riding Freedom

Riding Freedom Mañanaland

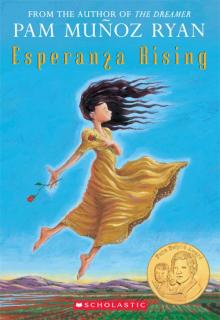

Mañanaland Esperanza Rising

Esperanza Rising