- Home

- Pam Muñoz Ryan

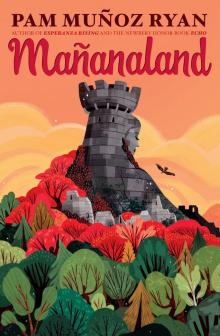

Mañanaland Page 2

Mañanaland Read online

Page 2

Max laughed. “Ortiz, you better hurry if you want to catch up to him. He played for the professional club, Los Lobos, when he was only fourteen. And the national team when he was eighteen.”

“Your grandfather played against him at El Coliseo, the giant stadium!” said Gui.

“Right. In a tournament game,” said Max. Buelo still carried the worn photo in his wallet of him and the phenomenal young footballer, Nandito, with their arms around each other.

“And your father played on the national team, too. He still holds two unbroken records,” said Gui. “One for most saved goals in a season and one for most saved goals in tournament play.”

“Fútbol is in your blood,” said Chuy.

Max hoped it was true. And that the talent hadn’t skipped him. If he made the village team and they won the championship again, he’d get his name and photo in all the newspapers. People would recognize him. Maybe even his mother.

“How come you don’t look like your father or grandfather?” asked Ortiz. “You’re so tall and skinny. Maybe you should play basketball instead.”

“Don’t listen to him,” said Chuy. “You’ve got talent running through your veins. He just doesn’t want the competition.”

“Your father only played professional for one year though,” said Gui. “Was he injured? I couldn’t find any record that he was released.”

Max hesitated. “He never talks about it.”

“My mom said he quit the team because he met your mother. Then she left him,” said Ortiz. “Some love story, huh?”

Max felt a jab in his heart. Everyone usually tiptoed around the subject of his mother.

Chuy raised both hands and made a sound of disgust. “Ortiz, what’s the matter with you? Your mother talks too much and so do you!”

“What? Everybody knows she disappeared. Anyway, who leaves the national team?” Ortiz began dribbling the ball from one side of the road to the other and back toward them. “But your grandfather played with Nandito! Not everyone can say that. I have a prediction. Someday I’ll make the national team, and you three will say you played fútbol with me.”

“Or you’ll be telling people you played with us,” said Chuy.

“Not likely,” said Ortiz, laughing and running ahead.

Chuy slung an arm around Max’s shoulder. “Tomorrow at one o’clock? We can practice and make plans for the bus ride to Santa Inés on Monday.”

Gui nudged Max. “Aren’t you excited?”

Max nodded and grinned. He was. And relieved that they had stepped away from talk of his mother. Any mention of her always surprised him, like the little toy he once had, la caja sorpresa—a box he cranked until a clown on a spring popped up when he least expected it—taunting him with buried questions.

Max dribbled the fútbol along the dusty path to the cottage, remembering the first time la caja sorpresa had burst open.

He was in grade two, playing marbles in the dirt on the playground with a new boy after school. All the other children had already gone home. A teacher sat nearby, waiting with them.

“My mamá is always late,” said the boy. “Where’s yours?”

Max frowned. “She lives far away.”

“Where?”

Max shrugged. Why hadn’t Papá told him?

The boy laughed. “You don’t know where your own mother lives?”

The teacher jumped up, quickly pulled the boy aside, and whispered something to him.

Solemnly, the boy nodded, then returned to the marble game.

“What did she say?” Max whispered.

“That you’re a poor motherless child and it’s not polite to talk about her.”

“How come?” asked Max. Other kids had parents who didn’t live with them.

The boy shrugged. “She said it might make you feel sad and unworthy. Want to play tag?”

As they began chasing each other, Max thought about what the boy had said. It wasn’t sadness he felt. It was a peculiar nothingness tucked behind a veil of secrecy that no one was willing to lift. Not Papá. Not Buelo. Not his neighbors or teachers. What did they know that he didn’t? He ran after the boy and the words echoed … poor … motherless … unworthy …

Later, as he’d walked home with Buelo and Papá, he asked, “Why did my mother leave? Where did she go? When is she coming back?”

Papá looked startled. “Max, where is this coming from?”

Max repeated what the boy had said.

Papá stopped and knelt in front of him, his eyes desperate. “Please understand. I don’t have all the answers. I don’t know where she is, and I don’t know if she’s ever coming back.”

“Have you looked for her?”

“Of course. I’ve never stopped looking,” said Papá.

“So you can ask her to come home and we can be a family?”

Papá sighed. “When you’re older, I’ll explain more. But now, you and me and Buelo …” He put his hand over his heart. “… we are a family.” He stood and walked on.

Buelo took Max’s hand. “This is a very painful subject for your father. Can you see that?”

Max nodded. His eyes brimmed. “But I don’t know anything about her. I don’t remember …”

“How could you? You were not even a year old when she left,” said Buelo. “Your father will share more when you are both ready. I will talk to him. Would you like that?”

Max nodded as tears rolled down his face. “Did … did … she leave because of me? Because I was unworthy?”

Buelo pulled Max close and wiped his cheeks with his handkerchief. “Unworthy? No. You have never given anyone a reason to leave. The only thing you have ever given this family is joy. If your mother could see the fine boy you are, she’d be proud.”

Max leaned into Buelo’s chest. “Will I ever meet her?”

“Solo mañana sabe. Only the place we know as tomorrow holds the answers.”

It wasn’t much comfort. But all the way home Max clung to Buelo’s words and whispered, “Solo mañana sabe.”

Later, at bedtime, when Papá came into Max’s room to say goodnight, he sat on the bed. “I’m sorry I was so abrupt today.” He stroked Max’s hair. “I know you want to know more about your mother. Her name is Renata Esteban Córdoba. And … you have her eyes.” He put the leather cord with the compass in Max’s hand. “This belonged to her. It had been her mother’s. She treasured it and wore it all the time. One day she couldn’t find it anywhere and was devastated. After she left, I found it lodged behind a drawer in the dresser. I always hoped to return it to her someday. Until then, I think she would want you to have it.”

In the almost dark, Max could see Papá blinking back tears. He didn’t want to cause Papá any more pain, so he didn’t ask questions. He just hugged his neck.

After Papá left, Max studied the silver compass with its markings for north, south, east, and west. As he turned it, the tiny needle shimmied. Engraved on the back was an elaborate compass rose with eight points of direction. Papá had said he didn’t know if she was coming back. Was she waiting to be found? Maybe the compass would guide him toward her, wherever she was, and Max could return it. When she met him and realized what a fine boy he was, she might even consider coming home.

Max whispered her name over and over so he could hear it rolling off his tongue. “Renata … Renata … Renata …”

The nothingness that he had felt for so long had turned into a little something.

The smell of peppery fish and fresh bread greeted Max before he reached the front gate.

Dinner and excitement about the fútbol clinic overshadowed his thoughts. Still, Max knew he would have to wait for the right moment to ask permission.

Buelo had been busy today. The yard was weeded, the bushes pruned, and the nearby corral for their burro, Dulce, raked. The small stable even had new straw. Max unlatched the front gate and Lola leaped toward him, shimmying and yelping as if it had been days instead of hours since she’d last seen him.

“I missed you, too, girl.” Max ruffled the dog’s black-and-white head and kissed her giant muzzle. She darted away and returned with a stick in her mouth, nudging his hand. Max tossed it as far as he could, and she ran after it.

Buelo hobbled from the stone cottage. Even with his cane, he liked to say he was as strong as Dulce, just a little slower. His shirtsleeves were rolled up, and a kitchen towel stained from cooking was tucked into the waist of his blue jeans. His wavy white hair seemed to float on his head like a cloud.

“Are you hungry? I caught trucha this morning, your favorite. Junior will be happy, too. Where is he? You beat him home.”

Everyone called Papá Junior because he was Feliciano Córdoba Jr., after Buelo, who was the first. Max thought the name Feliciano, which meant happy, fit Buelo much better than it did Papá. Max’s middle name was Feliciano, which seemed right, because he was somewhere between Buelo and Papá on the happiness scale.

“Yes, I’m hungry!” Max’s mouth watered at the prospect of fried trout. He followed Buelo inside the stone cottage, which, even during the warmest weather, stayed cool. After Max washed his hands in the sink and set the table, Papá finally walked into the kitchen. He held up a basket covered in a dish towel. “I saw Miss Domínguez.”

Max rolled his eyes. “Again? She was my teacher. It’s embarrassing!”

“It shouldn’t bother you. She’s not your teacher any longer,” said Papá. “And she only told me how much she is going to miss you in her class next year. She said you were very innovative in your approach to solving problems.”

Max hid his smile and thought better of telling Papá what she meant. Miss Domínguez had been amused by Max’s elaborate explanations for why he was late, or had forgotten his homework, or why he and Chuy should be partners for one project or another. She encouraged his storytelling. Papá, though, would think it immature. “She’s being nice because she likes you,” said Max.

Papá shook his head. “It’s just people helping people. She sees a boy like you and it brings out the mother hen in her. That’s all. Some fresh tortillas or bread. A knit hat or sweater. What does it hurt? And I’m helping to repair her garden wall. Favor con favor se paga.”

“A favor for a favor,” said Max. “I wish she’d repay you by sending a pair of Volantes in her basket.”

Buelo patted Max’s shoulder. “Volantes, so your feet can fly. I like your optimism. Now, both of you, sit. Tell me about your day.”

“We saw a giant falcon,” said Papá. “Female.”

“It was gliding in circles.” Max waved his arm in the air to demonstrate. “Papá said it was a peregrine. Then I saw it again when I was with Chuy, Ortiz, and Gui.”

“Twice in one day? Very auspicious,” said Buelo. “It’s known as the pilgrim bird because it journeys far away to promised lands but always returns to the same area, bringing good fortune and magic. You were lucky to see one.”

Papá raised an eyebrow at Buelo then turned to Max. “It’s just a myth. It was a coincidence. We happened to be there when it flew over. Only fools believe in luck. Good fortune comes from hard work, careful preparation, and practice.”

Max glanced at Buelo and rolled his eyes. Couldn’t Papá believe in something as simple as a little good luck?

“I am starting a new footbridge near the outdoor market next week,” Papá continued. “That bridge, not the falcon, will bring prosperity to the village by making it easier for people to trade and sell.”

Buelo grinned. “The new bridge will allow one side of the river to safely hold hands with the other …”

Max chimed in, “… because a Córdoba bridge never collapses. First things first, then stone by stone. That’s how to accomplish anything well.”

“That’s right,” said Papá, nodding proudly.

Papá, Buelo, and his father before him were stonemasons. They kept all the bridges in the land in good repair and built new spans. Already Max knew the best rocks for decking, revetments, and keystones. People often asked him if he was going to follow in his family’s footsteps. He never knew quite what to say. Maybe someday, after he became a famous footballer.

But first things first. Max took a deep breath and sat a little straighter. “Papá, tryouts are coming up and …” Max cleared his throat. “I need to get in shape and build my strength to be ready.” He held up a skinny arm, making a fist to show how much muscle he did not have. “Ortiz’s cousin is running a summer clinic in Santa Inés and said he can bring some friends. He invited me and Chuy and Gui. We’d take the bus there and back each day. Can I go, Papá?”

Papá didn’t even look up from his dinner. “It’s too expensive and too far away from home for you to be on your own.”

“That’s the thing,” said Max, leaning forward. “There’s no tuition! The cousin has extra spots to fill. I wouldn’t be alone. I’d be with my friends. You can talk to Ortiz’s father about it.”

Papá’s body tensed. “The answer is no! It does not matter whether it’s free or not. It’s in a town forty-five minutes away. Anything could happen to you in Santa Inés. And I know Chuy’s parents. I can’t imagine they will allow him to go either. Besides, Buelo and I can teach you everything you’d learn at the clinic. You have the expertise of two professionals right here in Santa Maria.”

“Papá, please …” Max begged. He looked to Buelo for help, but he only lowered his eyes. This was Papá’s decision. “You never let me do anything away from the village! You don’t need to worry about me. I’m responsible and I’m not going to disappear like—” Max regretted his words the second he said them.

Papá lay down his fork and stared at his plate. Finally, he looked up and said, “It’s others I worry about, Max. And the answer is still no. But …” He pointed at him. “You can work for me this summer on the new bridge. I haven’t hired an apprentice yet. Then you could earn new fútbol shoes. And lifting stones will build your muscles.”

Max slumped in his chair. He could see that Papá wasn’t going to change his mind. But if he was right about Chuy’s parents, at least Max and Chuy would be together. “Can Chuy be an apprentice, too?”

“If his parents agree,” said Papá. “I could use the help. I’ve already cleared the site. And the foundations and abutments are laid and mortared. I’m going to the ruins on Monday to collect more stones. You two can start unloading them at the bridge site after that.”

“Can I go with you to collect the stones?”

“You know the ruins is no place for a boy.”

“Papá, I’m almost twelve. I’m not little anymore.”

“When you’re older,” said Papá, the tone in his voice saying the subject was closed.

Max didn’t press because he knew it was useless. “We could work until the tryouts. But if we make the team …”

“Then I’ll hire an apprentice,” said Papá.

Buelo raised a finger. “Speaking of that, I heard about the new coach today.”

“Me too,” said Max. “His name is Héctor Cruz and he’s really strict about the rules. We have to prove our age and where we live just to register for tryouts. Everyone needs their birth certificate.”

“Our team has always respected the rules,” said Buelo.

Max continued. “But some teams didn’t and some boys were older than they were supposed to be. I wish Ortiz was too old to play. He’s trying out for goalie, too. He’s a lot bigger than me and has a mustache!”

“Bigger doesn’t mean better,” said Buelo. “Quickness counts.”

“Today I saved more shots on goal than he did,” said Max.

“See,” said Buelo.

“But he was better at throwing and kicking.”

“Max, you are skilled at forward, too, not just at goalie,” said Papá. “And keep in mind that not everyone makes the village team the first year they try out. It’s better not to get your hopes up. Besides, you’re still pretty young to be on a team that travels around the state. I’m not sure how I feel a

bout that.”

“You played on the village team when you were my age.”

“That was different.”

Max felt heat rise to his face. Different how? Why couldn’t Papá have faith that Max could look out for himself? Why couldn’t Papá be a little optimistic? “I want to make it this year! And play goalie like you and Buelo. If I make it, one of you would come to every game anyway.”

Buelo muttered, “He’s persistent, Junior, like someone else I know.”

Papá sighed. “True enough.”

“Can you start training me and Chuy tomorrow?”

Papá nodded. “As long as we get home by three o’clock. Your aunties and uncle are coming for dinner. And your uncle and I are going to play a little chess. It’s time I won a game from Mayor Rodrigo Soto.”

Max smiled. His aunties were really his great aunts—Buelo’s sisters, Amelia and Mariana. Amelia was married to Tío Rodrigo, the mayor of Santa Maria.

“Plus, you need to give Lola a bath tomorrow afternoon.” Papá pushed up from the table. “I won’t be late tonight.” He pointed to Buelo. “Don’t fill his mind with nonsense.”

“Stay out as long as you like,” said Buelo.

Before he left, Papá kissed Max on the head. “Go to bed when Buelo says.”

Max nodded, stealing a look at Buelo, who winked at him.

Buelo and Max made themselves comfortable in their usual places—Max on the sofa and Buelo with a cup of coffee in the overstuffed chair that sagged in all the right places.

Lola walked in circles and finally lay on the tiles in front of the fireplace. This time of year the firebox was cold, and the grate cradled only brooms of herbs that Buelo had collected. Max caught a whiff of dried rosemary, which always made him think of summertime and storytelling.

“You first,” said Buelo.

“Today I was wondering about Río Bobinado.” Max told him his story about the gargantuan serpent with the indecisive spirit creating the chasm that became the coiling river.

Buelo nodded. “A serpent that could not make up its mind. Perhaps that is why anyone who travels the river’s path is plagued with uncertainty and apprehension.”

Paint the Wind

Paint the Wind Becoming Naomi Leon

Becoming Naomi Leon Riding Freedom

Riding Freedom Mañanaland

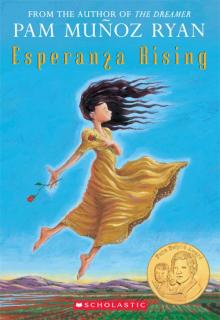

Mañanaland Esperanza Rising

Esperanza Rising