- Home

- Pam Muñoz Ryan

Becoming Naomi Leon Page 3

Becoming Naomi Leon Read online

Page 3

Fabiola stood up and gave Gram a big hug. Gram’s eyes watered up.

Fabiola hugged me and Owen, too. Then Bernardo walked us all the way to the edge of the grove.

Gram swiped at her eyes in the dark of the trees. I had never once seen Gram cry from sadness and was not accustomed to seeing her unsettled by her emotions. My insides wobbled as if I was standing on a three-story roof looking down.

After I was in bed, I closed my eyes but couldn’t sleep. I tried as hard as I could to remember something about my mother. Memories from a place far away in my mind struggled to get to the front of my brain, but they swam in slow motion, stroking through thick syrup toward my clear thinking spot. All that surfaced was my past imaginings of what she might be like.

Over the years, the top three on my preferred list of “Possible Moms” were 1) Volunteer, 2) Business, and 3) Nursery. I had pretended she was one of those smiling moms who came to school twice a week, volunteered in class, and helped with yard duty. She invited my friends over after school and was president of the Parent/Teacher group, and all the teachers fought over me every year because they knew if they got me in their class, they would get my wonderful mom, too. Sometimes I imagined a business mom who wore suits, fancy scarves, diamond earrings, and high heels that clickety-clicked down the halls. She would visit my class on career day and talk about her important job in a big office in San Diego. I even thought she might be like some of the moms who worked in the plant nursery nearby. She’d wait on the corner to walk Owen and me home from school every afternoon, wearing a green-stained apron and holding a bouquet of flowers.

But right off the mark, Skyla didn’t match my list or fit the pictures in my mind.

I did have one recollection of my father and Mexico. Owen and I were huddled in a room near the ocean. I could hear thunder and lightning and waves crashing. It was raining so hard that the roof leaked, and when I looked up through the sprinkles of water I saw a swirl of color — a bobbing, dangling dance of pink and blue and yellow above my head. What could that have been? A dream? I remembered Owen pointing to the ceiling and laughing in that way he had, like a batter of coughing and giggling. I rocked him, afraid to move off the bed. I cried and cried until our father rushed in.

He swooped us up into his arms and took us to an old church where people had gathered, seeking safety from the storm. We were in a basement, cots set up in rows, and women serving soup. I remembered crying into my father’s flannel shirt, which tasted salty. To get my mind off the thunder and lightning, he found a bar of soap and carved an elephant. He gave it to me, and I fell asleep clutching it. When I woke up, he was gone and never came back. Bernardo always said my talent for carving must have passed from my father’s hands to mine. I would have rather had my father.

I pried the rest of the story out of Gram when I got older. She explained that our father had been out on a fishing trip and our mother was supposed to be watching us. She had taken off though, on a shopping trip to Tijuana and left us alone to baby-sit ourselves in the motel room. Then the storm hit. Nobody could find our mother for days. She finally showed up at the church a week later, packed us up, and took us back to Lemon Tree. She told Gram that she couldn’t handle two kids by herself, especially with one of them deformed. A few days later she was gone, too.

I squirmed in bed, trying to get comfortable, but my mind was still a jumble. I finally got up and pulled a box from the drawer under my bed. I opened it and carefully dug through my soap carvings of turtles, dogs, and reptiles, and pulled out a family of elephants. I arranged them on the built-in shelf above my bed, all in a line, trunks to tails. Then I put my head down on my pillow and closed my eyes, the caravan of milky statues guarding my dreams.

In the morning I tiptoed into the living room/kitchen. Skyla rested peaceful on the foldout, her hair making a splash of almost-purple on the pillow. Without makeup, she looked younger than last night. Lying on one side with her legs pulled up a bit, the curve of her body made an empty space, like a little nest in the middle of the bed. I wished she was awake and we didn’t have to go to school. I had visions of Owen, my mom, and me all huddled up together, giggling and telling stories.

I stared at Skyla for so long that I didn’t notice Owen standing at my side until he nudged me and handed over a box of cereal.

Through the small, slatted window, I saw Gram watering the bird-of-paradise plants that grew on the side of the trailer. We fixed our bowls as quiet as we could and went outside to sit on the patio couch under the trailer awning.

Gram came around and sat opposite us in the two-person swing.

“Was she stirring?” Gram nodded toward Baby Beluga.

“She’s sleeping,” said Owen.

Gram cleared her throat like she was going to make an announcement. “When Skyla came in late last night, we had a heart-to-heart. She has assured me that she just wants to spend a little time with you. I am going to give her the benefit of the doubt and see how she behaves. I think that’s the right thing to do. Besides, you both must be natural curious about your mother.”

I set down my cereal bowl and walked over to Gram and hugged her hard and didn’t let go.

“Don’t you worry, Naomi,” said Gram, patting my back. “We’re going to weather this. Let’s just plant plenty of sunshine in our brains.”

I squeezed my eyes shut. I planted the image of me showing Skyla my carvings, one by one, and her fussing over my talent while I shined, proud as punch.

Mrs. Maloney tapped on her bedroom window, breaking my concentration. She waved at us, then pointed at Owen.

“I almost forgot,” said Gram, looking at Owen. “Mrs. Maloney needs help moving her hummingbird feeder. She loves watching them through the window, with all their flitting and shimmering, but they’ve taken to diving and pecking at Tom Cat. I told her you’d be over after school.”

Owen nodded to Mrs. Maloney and waved back to her.

“Will Skyla be here for dinner?” I asked.

“I don’t know her plans, Naomi,” said Gram. “But I’ll make a point of inviting her.”

That evening we were almost finished eating Thursday pork chops when we heard Skyla’s car pull onto the gravel. A minute later she burst into the living room/kitchen with her hands full of shopping bags.

Gram, Owen, and I froze with our forks in midair, just like one of those commercials on television.

“Hi, everybody. I’ve been shopping! Naomi, get over here and see what I bought you!”

Skyla dropped the bags and began pulling clothes from them. “Oh, this one’s for me. But here, this one’s for you. What do you think of this cute top? And these jeans are perfect. I hope they fit.” She held them out to me.

I had been wearing Gram’s homemade clothes and the ones from the Second Time Around Shop for so long that I couldn’t believe someone was handing me a brand-new pair of store-bought jeans.

Skyla looked at me and said, “Well? Are you going to just sit there? Come back to the bedroom with me and try these on.”

Gram’s eyebrows peaked with surprise.

I hurried to the bedroom and tried on the jeans.

“They are perfect!” said Skyla. “Now, try on this top. If it fits, I’m going to buy you a few more.”

The light-pink stretchy top had little rhinestones in a butterfly pattern on the front. I had seen one in the window of Walker Gordon, but I never dreamed I’d have one of my own.

I walked out to show Gram and Owen. Skyla followed me.

Gram had her back to us, standing at the sink.

Skyla cleared her throat and said, “And here she is, star of screen and television!”

Gram turned around and smiled and clapped her wet hands together. “Why, don’t you look spiffy! And Owen?” Gram said, as if signaling Skyla not to forget him.

“Oh, today was shopping-for-the-girls day. Next time I go, I’ll shop for Owen.”

Owen grinned at Skyla and said a little too loud in his raspy voice, “Than

k you!”

“Is there something you’ve been wanting?” asked Skyla.

Owen ran to his room and came back with a magazine picture of a bicycle and held it up to Skyla. “Naomi and me love to go to Dan’s Bike Shop and look at new bikes,” he said.

“Owen,” said Gram. “I’m not sure that’s in the price range Skyla had in mind.”

Skyla nodded at Owen. “Well, that’s something to think about. Now, Naomi, why don’t you let me do something with your hair.”

“It’s a troublesome mess,” said Gram. “I’d love to see it off her face.”

Skyla laughed. “I have French-braided the wildest heads you’ve ever seen. Sit down and let me get started. Are you tender headed?”

“No,” I said, pulling out the half-dozen clips and situating myself cross-legged in front of her.

As Skyla brushed out my tangles, I couldn’t help thinking over and over that my mother’s hands were on my head. She took a fine-tooth comb and pulled it through my hair until there wasn’t the tiniest knot anywhere. Then she started at the center top, bringing up tiny strands of hair, one over the other. Her fingers were nimble and gentle. It felt as though she was playing the piano on my head. The little finger kept reaching lower and lower, carving out sections to braid into the rest.

In a matter of minutes she said, “All done and don’t you look pretty. Here, take this hand mirror so you can see the back.”

I jumped up and ran into the bathroom. There wasn’t one strand of hair out of place, and the braid was woven like the rolled edge of a basket.

I patted and admired it for fifteen minutes straight.

Skyla came in and stood behind me and looked in the mirror. “Naomi, you have a perfect heart-shaped face. Did you ever notice that?”

I had not ever noticed, but now that my hair was pulled back tight, I could see that she was right.

“Now, stay with me while I freshen my makeup. Clive and I are going out, and I want to look perfect.”

I watched her put on the base and the blush and liner and eye shadow, which took over half an hour. She gave me some clear lip gloss called Wet As A Whistle. I put it on, then took it to my room and put it in my backpack. I couldn’t wait to put it on at school in front of the other girls.

Back in Gram’s bedroom I watched Skyla squeeze into her jeans and boots, then gather her purse and jacket.

“How do I look?” she asked, smiling.

“Nice.” I nodded, the braid tickling my neck. Then I followed her into the living room/kitchen.

“Where’s Owen?” said Skyla. “I have something to tell both of you.”

“He’s trying to coax Mrs. Maloney’s cat out from under her trailer,” said Gram. “Poor old Tom is scared to poke his head out for fear of a hummingbird attack.”

“Well, that’s neighborly sweet. Naomi, I’ll tell you and you can pass it along. I saw on the fridge that your teacher conferences are a week from today. Next Thursday, right? I am planning on being there with Gram to see your school and meet your teachers. Isn’t that great? I am looking forward to it. I’ve got to run on to Clive’s right now but I’ll see you all later. Bye.”

After she shut the door, I could still smell her gardenia perfume.

I sat down next to Gram. She patted my knee and looked me up and down once more. Smiling and shaking her head like she was trying to figure out a puzzle, she said, “It’s real nice that Skyla wants to go to your conferences. What do you think about me staying home, just this once, so she can have some special time with you kids?”

“Okay,” I said. “I could show her my clay sculpture in the art room.”

Gram kissed me on the forehead. “Your hair looks pretty as a picture. Are you going to wear your new ‘do’ to school tomorrow?”

I quickly nodded and wondered if anyone would notice the difference.

The minute I walked into the classroom, Ms. Morimoto said, “Naomi! Your hair looks lovely like that!”

I smiled at her and walked to my seat.

Ms. Morimoto was a Japanese version of Fabiola. She had the same exact curly hair, and instead of long aprons, she preferred flowing skirts in bright colors. Students at Buena Vista Elementary prayed to get assigned to Ms. Morimoto for fifth grade, because every year in January she took the whole class out to dinner at a fancy restaurant and to a play at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego. It was her claim to fame. Besides that, she was nice and didn’t take any nonsense from the troublemakers.

One of the boys from the back of the room yelled, “Ooooo, Naomi!”

The boys all laughed, but the girls didn’t, and I could see they were inspecting me top to bottom. Sensing their stares, I sat down right away and busied myself with looking in my desk until the start bell rang. I was secretly smiling, but I sure wished I could control the warmth crawling up my neck and cheeks.

Ms. Morimoto clapped her hands to get our attention.

“People” — she always called us people — “I’d like you to meet a new student who has just transferred to Buena Vista. Blanca Paloma. She comes to us from Atascadero, California. Please make her feel welcome. Blanca . . .” Ms. Morimoto looked toward the side of the classroom.

A skinny girl with long black hair, even curlier than Fabiola’s or Ms. Morimoto’s, stood up and quickly sat back down.

Maybe it was my French braid, or maybe Blanca didn’t know yet that I wasn’t one of the makeup-sleepover girls, but at morning recess she came right up to me and started chattering away. I didn’t understand two words she said.

“I don’t speak Spanish,” I finally told her.

Like a light flicking from off to on, she changed to English. “You’re not Mexican? Funny, you look Mexican. We just moved here, you know. My mom works for ValueCity. Know what my name means in English? White dove. What’s your name?”

“Naomi Outlaw.”

“Wow, you talk so soft. Get closer so I can hear you better. Just Naomi Outlaw? No middle name?”

I took a step closer and gave her the full version. “Naomi Soledad León Outlaw. But I just go by Naomi Outlaw.”

“León. That means lion. You’re Naomi the Lion.” She wasn’t making fun, just saying it matter-of-fact.

“What’s Soledad mean?” I asked.

“Soledad is some big saint in Mexico. Men and women are named after her. I have an Uncle Soledad who raises goats. They stink.”

I laughed.

“Who did your hair like that? It looks amazing.”

“My mother,” I said, the words sounding as strange as Spanish on my tongue.

“My mom never learned French braiding because she works all the time. I go to the Y for the before- and after-school programs. It’s just her and me because she’s divorced from my dad. We’ve lived in Walnut Creek, Riverside, Atascadero, and now Lemon Tree, all in two years. She’s moving up in the company. So, is it just you and your mom, too?”

“I live with my gram and my brother, but right now my mom is visiting.”

“Just visiting? How come she doesn’t live with you?”

“She . . . she . . . left us with my gram when we were little.”

“What about your dad?” asked Blanca.

“Divorced.”

“Same as me. I don’t see my dad very much. What’s yours like?”

“I don’t know. He lives in Mexico. He’s never come to see us.”

“You don’t know anything about him? You should ask, that’s what my mom always says. Ask lots of questions and you’ll get lots of answers. You deserve to know about your own life. Right?”

“You don’t know my gram. She’s doesn’t like to dig up old bones.”

“That’s funny. Dig up old bones. Hey, I heard we’re having conferences next week. Maybe our moms could meet? Then they could arrange for us to get together. What do you think?”

“Maybe,” I said. Should I tell Blanca I had only known Skyla for two days?

“Have you ever been to Mexico?” asked Blanca. “In my w

hole life I’ve never been. My dad promised he’d take me someday. Hey, did you know I get a discount on anything at ValueCity since my mom’s a manager?”

Gram would call Blanca a jabber-mouth, but I liked her and was already hoping she would stick close to me all day.

I didn’t have to worry. At lunch she grabbed her bag and stayed on my elbow until we reached the library.

Mr. Marble looked at me and said, “And who is this person with the elaborately plaited hair?” Then he bowed to Blanca. “Ah, the new student. I heard about you in the staff room this morning. Welcome to our safe haven. Is there a particular subject you are interested in, Blanca, because if so, I can highly recommend a book on just about anything. After all, I am a librarian. Since it’s lunchtime, can I interest you in some mind food? Or, since we have an aquarium, I could also offer you some fish food.”

We both giggled and sat down at a table.

“Wow. You eat in here?” said Blanca. “Like a club, huh?”

I had never thought of it that way. I just thought it was where all the leftover kids ate.

While we took out our sandwiches, Mr. Marble arranged the glass display case. First he stacked a bunch of little boxes inside and covered them with a giant silky red scarf. Then he placed dolls dressed in costumes from different countries on the little boxes.

“These are Ms. Domínguez’s private collection. Ms. Domínguez in case you don’t know, Blanca, is our principal. She collected these as a girl. Now, everyone close your eyes. I am going to add some ambience.”

We closed our eyes.

“Ta-dah! What do you think?” he said.

When we opened our eyes, he had turned on the light inside the display case. The light reflecting against the scarves made the dolls shine with a rosy glow.

I nodded my approval.

Mr. Marble changed the case every few weeks, and he always decorated it perfect so a student just couldn’t resist stopping and looking inside. Sometimes, if Mr. Marble knew that a student or a teacher had a collection of some kind, like rocks or baseball cards, he would display them. My dream was to make it to the glass case at the library and to be known for something other than my current reputation as the weird kid’s sister with the funny last name, who wore clothes that matched her great-grandma’s polyester wardrobe.

Paint the Wind

Paint the Wind Becoming Naomi Leon

Becoming Naomi Leon Riding Freedom

Riding Freedom Mañanaland

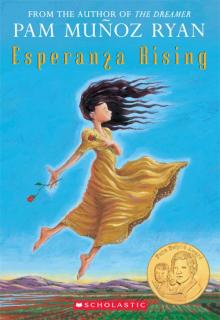

Mañanaland Esperanza Rising

Esperanza Rising